Disclosure: I am a happy paying member of Ridwell. I am extraordinarily annoyed at every waste management company’s attempts to stop Ridwell from recycling items they refuse to/are to lazy to recycle (which also stops Ridwell from redistributing still-useful items). Some of the companies have threatened to sue or actually have sued.

Maybe you’re like me: I try to avoid excess plastic with my purchases when I can, I try to patronize businesses that try to avoid plastic, I don’t use the plastic produce bags. Yet neither of us can avoid generating any plastic waste at all–and for us (for me, at least) it’s not a realistic option. We can’t choose how our prescriptions are packaged (we can’t even avoid the totally unnecessary plastic birth control pill dispensers). We can’t choose a “plastic alternative” if we need to use an ostomy appliance or get a blood transfusion or need to be intubated. We can’t opt out of plastic

Curbside Recycling?

KNOW THE RULES! I’ve lived in multiple houses, dorms, and apartments in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Texas, California, and Oregon. In each place the rules for recycling varied wildly, sometimes differing dramatically from one town to the next one a few miles over. If you have access to curbside recycling (I remember in one place it was optional and cost extra–WTF??) I hope you’re both using it AND using it correctly. For most of my life to determine whether I could recycle a plastic I had to look at the logo with the arrows and see what number it was; mostly, #1 and #2 were a go, and the rest were a no.

Imagine my surprise when I moved (back) to Portland, only to discover that in Portland, the numbers are irrelevant and it is the shape of the container that matters!

According to the official website for the City of Portland, “When sorting your plastics, ignore the recycle symbol and number: Plastics recycling in Portland is based on the size and shape of the item. Please rinse containers. They do not need to be perfectly clean, but should be free of food residue and dry before they go in your bin.” Um, really? Yes, really.

Oregon Metro explains it this way: Ignore the numbers. Ignore the arrows. Sort by shape. These items are OK in your recycling container–rinse thoroughly.

Plastic bottles, jugs and jars 6 ounces or larger, any container with a threaded neck (for a screw-on lid) or neck narrower than the base. This includes milk jugs, peanut butter jars, and bottles that held personal care and cleaning products (shampoo, laundry soap, etc.).

Round plastic containers that can hold 6 ounces or more, with a wider rim than base, and typically contain products such as salsa, margarine, cottage cheese, hummus, etc. (no drink cups).

Planting/nursery pots larger than 4 inches in diameter and made of rigid (rather than crinkly or flexible) plastic. Remove any loose dirt.

Buckets 5 gallons or smaller. Handles are OK.

(Incidentally: the fact that I can put something into my recycling bin does not mean it is, actually, factually, really, truly, recycled. Given the absolutely abysmal rate at which plastics are recycled–check out what Consumer Reports has to say about how little plastic was recycled in 2018–I doubt it’s very much. It didn’t get better when China started to refuse loads of plastics from the U.S. It didn’t get better during the global pandemic. I’d love Waste Management, my curbside provider, to provide data on when, where, and how much of the collected plastic is recycled. Unfortunately, that transparency remains lacking.)

What I Can Recycle in NE Portland

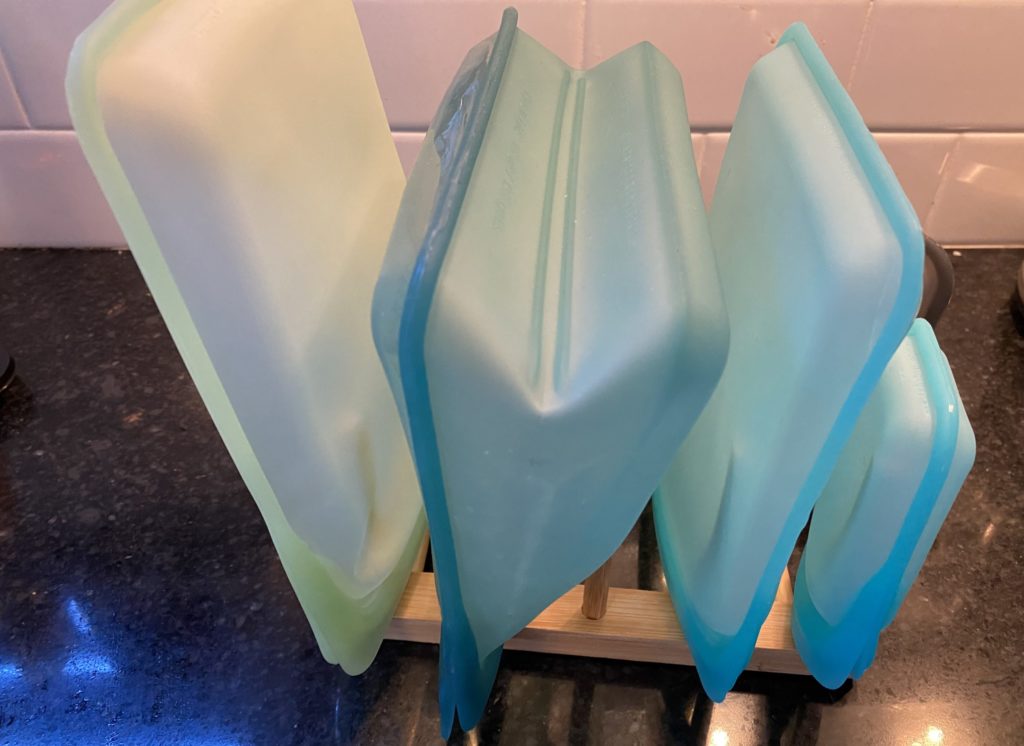

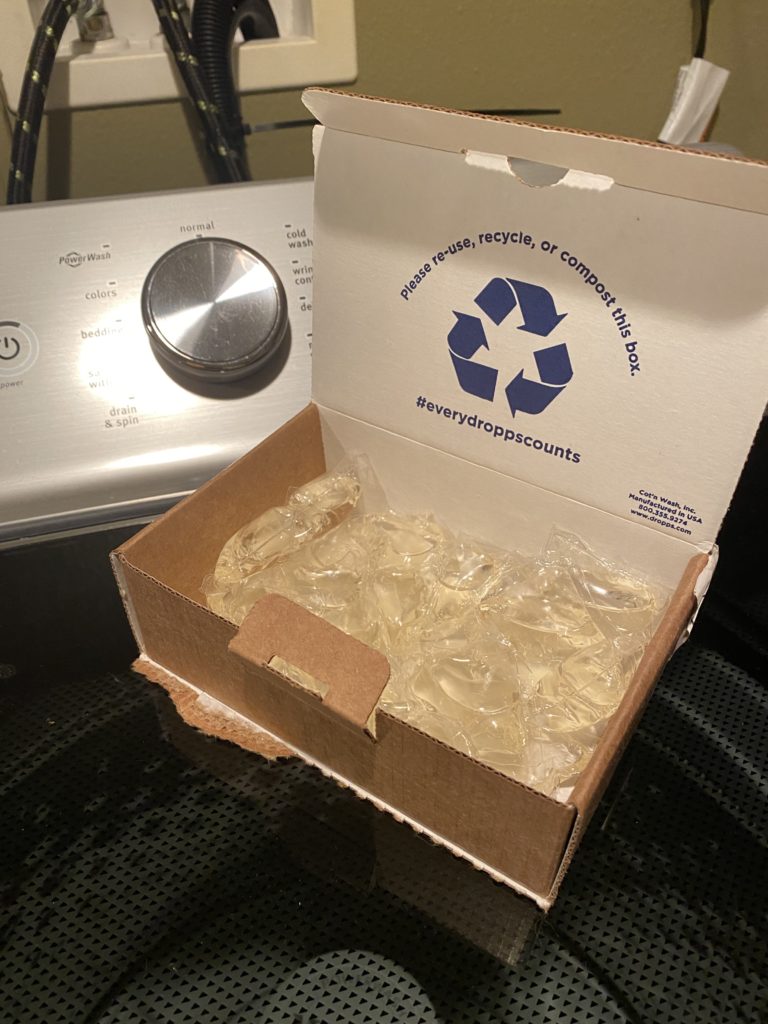

Okay, so both in Portland and the Oregon Metro area, I can avoid using a decent amount of recyclable plastic. I use shampoo bars, Blueland hand soap and toilet cleaner, and Dropps laundry products and dishwasher soap; I put my plastic deposit containers into a blue charity fundraiser bag and take them to a Bottle Drop drop-off location (like at the grocery store).These cover the main categories of what I can put into my recycling bin. I’m a bit stuck when it comes to some of the things that come in plastic tubs.

What I CANNOT Recycle? Everything else. According to Metro, that’s:

Any plastic that is not shaped like a bottle, round tub, bucket, or jug :

- NO plastic bags or plastic film of any type: pallet wrap, bubble wrap, stretch wrap (think: Amazon bubble mailers, the air cushions in packages)

- NO plastic caps or lids

- NO plastic 6 pack can holders (all types, including rigid plastic)

- NO plastic take-out food containers and disposable plates, cups, and cutlery

- NO prescription medicine bottles and other plastic containers under 6 oz (think: no contact lens solution, no travel-sized anything)

- NO disposable plastic or latex gloves

- NO bottles that have come in contact with motor oil, pesticides or herbicides, or other hazardous materials

- NO hoses, ropes, or cords

Some of these things are avoidable, but others are not. Just try to buy a loaf of bread (the regular sliced kind, not the fancy artisan rock-hard-in-two-days kind) without a plastic bag. Or a jug of milk without a cap. It’s not like you can order online and avoid bubble wrap or “plastic pillows” entirely.

Ridwell: Supplemental Recycling

Since I can’t avid plastic bags or film, plastic lids/caps, and many of the other items, what’s a smart woman to do? Join Ridwell.

Ridwell is essentially a supplemental recycling service. Every two weeks they pick up plastic film (that’s bubble wrap, bread bags, etc.), batteries (which should never go into a landfill or dump as they release chemicals that form a hazardous toxic soup), light bulbs (samesies!), and “threads” (clothing, fabric, shoes). These are part of my core service, and I paid around $100-125 for an entire year of service (26 pickups). I have a porch box, and a (washable, reusable) cloth bag for each of the core categories. If I have more stuff than my porch box can hold, I can add a bag for $1. I also have the option to add a (separate) bag of plastic clamshells (like strawberries come in at the grocery store) for $1, a large bag of styrofoam pieces for $9, or fluorescent light tubes (starts at $4).

In addition, each pickup has a “featured items” category. A few things I remember in that category: crayons, Halloween candy, corks (like from wine bottles), metal bottle caps, plastic bottle caps, prescription medicine bottles, holiday lights, winter coats, electronics, school supplies, sports equipment, bicycles and bike equipment, diapers, bread bag tags, toiletries, kids books, non-perishable food. There have been more. It includes many hard to recycle plastics. Many of these items are not recycled, because they are still reusable; so they are distributed to non-profit partners in my area.

Ridwell sends customers a newsletter with information on what percentage of the core categories gets recycled. There’s also a blog with articles about Ridwell’s activities, and my account page links to a page about the Ridwell partners in Portland, such as PDX Diaper Bank, Children’s Book Bank, and WashCo Bikes.

So, for example, in May I got an email that informed me: ” You packed our warehouse sky high with clean, compressed #1 PET plastic. Together, we diverted over 112,000 lbs (>56 Tons) of clamshell plastic waste from landfills. Instead, the clamshells were recycled by our partner, Green Impact, and given a second life as 2 million new containers, protecting your favorite berries and snacks. This is all thanks to 25,000 Portland members, like you. Happy Clamiversary!” It also had a link where I could learn more about Green Impact. This is one of many such emails I have gotten from Ridwell. Transparency matters. (Too bad Portland’s contracted waste haulers are too busy protesting Ridwell to let their customers know where the recycling actually goes, eh?)

By the way, if Ridwell operates where you are, I think I still have a few opportunities to give you one month of free Ridwell. Drop a comment, and then shoot me an email.

Other Supplemental Recycling in Portland: James

Maybe you can’t get Ridwell where you live. I hope you have another option like James’ Neighborhood Recycling Service. James is a Portland resident who works in certain neighborhoods here. He runs a pick-up service and operates at community events. James can take all sorts of plastics for recycling, including things like cassette tapes, empty contact lens blister packs, styrofoam, straws, plastic utensils, and more. He takes electronics like batteries, lightbulbs, power cords, laptops, and more. James also accepts some other unusual, hard to recycle items including: wine corks, cereal bag liners, toothpaste tubes, floss containers, toothbrushes (non-electrical), inkjet and toner cartridges, pumps (from lotion, hand soap, etc.) and spray nozzles from non-hazardous products.

If you’re not in Portland, try running a search for local recycling options, community recycling, or similar. You might even have a zero waste group in your area that operates on Facebook, NextDoor, or another social media platform.

Plastic Film Recycling–Near You?

Avoiding plastic film is really difficult. (Bread bags, bubble wrap, etc.) Check out Plastic Film Recycling for more information and resources. To find a drop-off location to recycle plastic film, try the drop-off directory. (I found 160 locations near me, searching by zip code.) The directory also has a page for what falls into this category (yes to product wraps, air pillows, and plastic mailers) and what is excluded (no to frozen food bags, “compostable” bags, and six-pack rings).

If it seems like a pain in the butt to make a special trip for a handful of bread bags, why not reach out to your neighbors? If you have kids, they could turn it into a community service project with their Brownie Troop, Cub Scout pack, church youth group, school, or other organization.